by: Ji Ho (Geo) Yang, PHD Candidate at the University of Washington

Post 3 – If you haven’t read the first 2 posts from this blog series, I encourage you to read it before reading this finale. Many of the concepts and ideas talked about here are explained and defined in those posts.

As winter 2023 approached, I had to unfortunately depart (due to personal/health issues) from collaborative just before the codesign tires were about to really hit the road. I was blessed, however, to have a couple of opportunities to join the codesign space to see the project’s development later on. The codesign has not only taken off, it was truly cruising!

I joined a codesign session at Wing Luke Elementary in April 2024. At that point, families and students had developed a strong community. Members of the RCPP noted they felt a difference when the ELC sessions shifted to in-person, which led to the decision to move March, April, and June’s meetings in person as well. The community presence and cohesion were palpable, starting with a meal in the cafeteria and then transitioning into the library for activities. Families were vulnerable and sharing their own educational journeys, dreams for their children, and how schools and educational systems can better serve them. In their vulnerability, they shared the innumerable ways they teach, practice, engage, and create literacy practices. Kids were so joyous in having their siblings and families together in their school while enjoying each other’s company by talking and engaging in literacy activities rooted in their families’ stories and proverbs. For me, the joy, vulnerability, and greater community from that session were indicative of the intentionality of the codesign process from all stakeholders, including the considerations made by the RCPP throughout the codesign’s lifecycle towards the politicized nature of trust. The care put into relationship building and centering families’ wisdom was foundational to sustaining trust.

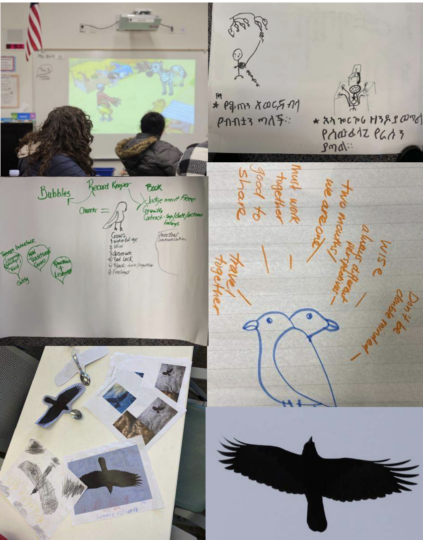

At this session, the summation of the codesign had already taken shape in the form of a story and book they have created, called Picksee: The Curious Little Crowthe “Picksee story.” Based on families’ proverbs and cultural stories, the book considers how Black children’s journeys of balancing their own cultural values and relationships (part of one’s home culture) while being open to learning new ideas and experiences through different cultures and institutions (e.g., school). The Picksee story was emblematic of many of the reflections families had from the first two co-design sessions. Embracing Black students’ home cultures, languages, spirituality, and intergenerational knowledge was a theme within the book and during April’s session. This story was powerful not only in its centering on the Black families and youth involved but also in the universality and meaningfulness of its theme for many other families and youth in our schools. The Black boys of the codesign team shared their thoughts on developing the story, reflections on its themes, and experiences designing and creating the Picksee story. They were proud and excited to have their families in their learning journey within school spaces. For them, the codesign process was a space for them to exercise agency in their own learning and transform how their school, teachers and principals, and district leaders engaged with literacy. This transformative agency, which relates to stakeholders’ capacity to enact meaningful and sustainable changes in their communities for social justice and equity, was dependent on ELC members, particularly Black families, to feel empowered to collaborate with each other, lead codesign, and impact their child’s learning and their school.

The final event of the 2023-2024 school year for the codesign collaborative was a June celebration at the Cypher Cafe in Central District to honor and highlight the tremendous journey the family and youth designers went on. The place was filled with people from all stages of the project chatting, laughing, and enjoying food and each other’s company. While similar to the launch a year ago, this celebration’s energy was more familial and buzzing. We celebrated the tremendous journey the ELC families and students went through, the relationships they built, and literacy practices that centers Blackness and their vision of learning. It was here that I actually had the honor and privilege to sit down with some of the families to talk about their journey, what they hope for their children in school and beyond, and what the Picksee story meant to them. Families and interpreters shared how they greatly appreciated designing a book and learning resources with their boys. While there was awkwardness during the first sessions on Zoom, families did not hesitate to share with me their emotions, experiences, and thinking now. Families and youth appreciated developing a Black-centric community that was across schools and encompassing the larger Black diaspora. This relationship-building process was also meaningful for families as they embodied and enacted leadership over time. Similarly to their boys, the families exercised agency (e.g. built relationships and leadership) that could influence how literacy is perceived and practiced at their school and district. The development of transformative agency of families and students within the codesign space was possible because Black families felt authentically empowered to collaborate with one another to genuinely impact learning in their children’s schools. The Picksee book is a summation of the codesign process where families’ and students’ sense of freedom expanded over time as relationships were continually cultivated, evident in reflecting on the launch to the celebration.

To see the project’s journey from its earlier days which was primarily comprised of university and district collaborators, to now, where families and youth lead the codesign process to teach educators, academic scholars, and system leaders was immensely amazing! The codesign process at the end of year 2 would not have been possible without the immense collaboration of educational stakeholders across SPS, UW, community organizations, educators, principals, and family connectors, and the continual recognition that Black families and youth are central to fostering early critical literacy. Year 2 is not the end, but only a cycle or iteration. The RCPP-ELC codesign project continues into year 3, including community readings and share-outs of the Picksee book. The ELC collaborates with the Seattle Public Library to organize a fall Picksee book event. It is exciting to witness where the Picksee book travels next (hopefully to our classroom libraries and homes) and exciting to see how the transformative agency of the codesign team will further transform our schools and classrooms into being culturally responsive, community-centered, and equitable.

I am immensely grateful to the RCPP and ELC for having me on their team. Thank you! I have learned much from my time with the codesign project, and hopefully, my participation impacted the project. This blog series is largely possible with the collaboration and blessing of the RCPP. Many of the reflections in this series are from my experience with the RCPP, including going back and analyzing field notes, session plans, codesign documents, etc. The learnings in this series were also directly from RCPP leaders (e.g., Drs. Habtom, Ishimaru, Nickson). Please contact the RCPP (linked in first post and below) for more information.

Websites (Mostly linked in blog):

https://www.education.uw.edu/pre/early-literacy-collaborative

References (Vakil et al., 2016 linked in blog)

Comber, B., Thomson, P., & Wells, M. (2001). Critical literacy finds a” place”: Writing and social action in a low-income Australian grade 2/3 classroom. The Elementary School Journal, 101(4), 451-464.

Kinloch, V., Penn, C., & Burkhard, T. (2020). Black lives matter: Storying, identities, and counternarratives. Journal of Literacy Research, 52(4), 382-405.

Roby, R. S., Calabrese Barton, A., Tan, E., & Greenberg, D. (2023). Co-making against antiBlackness. Equity & Excellence in Education, 56(3), 450-463.

Souto-Manning, M., & Price-Dennis, D. (2012). Critically redefining and repositioning media texts in early childhood teacher education: What if? and why?. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 33(4), 304-321.

Vakil, S., McKinney de Royston, M., Suad Nasir, N. I., & Kirshner, B. (2016). Rethinking race and power in design-based research: Reflections from the field. Cognition and Instruction, 34(3), 194-209.

Wynter-Hoyte, K., Braden, E., Boutte, G., Long, S., & Muller, M. (2022). Identifying anti-Blackness and committing to Pro-Blackness in early literacy pedagogy and research: A guide for child care settings, schools, teacher preparation programs, and researchers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 22(4), 565-591.

Yamashiro, K., Wentworth, L., & Kim, M. (2023). Politics at the boundary: Exploring politics in education research-practice partnerships. Educational Policy, 37(1), 3-30.